What the twenties are for has evolved over the decades. Gen Z is defining a new way of being twentysomething which learns from—and responds to—earlier conceptions.

“What were the most important lessons you learned in your twenties?” Aimee leaned forward in her chair as she stared at me through the computer. “No softball questions to get this interview started?” she asked me. I smiled in a way that said, “I’m sorry, but also, no.” Her opening line was one of my favorites:

“My twenties. (dramatic pause) What a shit show.”

Aimee, now 38, grinned and shared a series of hilarious and heartbreaking memories via Zoom from her home in Raleigh. Pictures drawn by her children decorated what I could see of her office.

Aimee has a strange sense of nostalgia for a time in her life that she didn’t actually like very much. She told me, “I mostly dated the wrong people, worked at a job I didn’t like, and fantasized about going to a grad school I could never afford to study a subject that would make me basically unemployable.” Even with this honest portrayal of her twenties, her stories were filled with sentimentality.

The potential within the pain

Nostalgia is strong once those years are in the rearview mirror, not only because of taut skin and faster metabolisms, but because in hindsight we become painfully aware that it was a time of unbridled potential. According to neuroscience, the brain isn’t fully cooked in the twenties, so great change remains possible as new connections are constantly formed.

“Never again will you be so quick to learn new things. Never again will it be so easy to become the people we hope to be,” wrote the clinical psychologist, Dr. Meg Jay, in her book, The Defining Decade.

Perhaps this is one reason why being twentysomething is glamorized by people not in them. For example, both 40-year-olds and 16-year-olds seem to want to look like 22-year-olds. But actually being in your twenties is a rollercoaster, particularly the catapult into the workforce. After two decades of having the cadence of life dictated by semesters, finals, and breaks, it’s hard to walk into the unknown and realize that you are in charge of your own life.

I recall a few years ago on a client project I was interviewing college new-hires to see what they thought of the onboarding program. In a moment of candor and fear, one young man said to me quietly, “so this is just what we do now? Forever? How do people live like this?” I believe the “this” that he was referring to was coming into an office, working on a computer for 8-10 hours, every day, forever, with two weeks of PTO. I jokingly replied, “Well, it’s not exactly like this. You got to play kickball today, for team building.”

How the twenties have changed

The twenties have been stressful for every generation—just in different ways. When I interview college-educated Baby Boomer women, they tell me about the intense pressure that many of them felt to graduate with an “M-R-S degree.” One woman shared with me strange (and fake) statistics that circulated around the University of Wisconsin-Madison in the 1970s that said if you left college without a husband, you were nearly guaranteed to never marry. Even at the height of the sexual revolution, many women felt a sense of panic.

Boomer men tell me about the pressure they felt to become the primary breadwinner of a household. In Baby Boomer interviews today, I ask, “What motivated you in the workplace when you first entered?” From the men, I mostly hear something like, “I had a mortgage to pay and a family to feed. That was the motivation I needed.” The majority of college-educated Baby Boomer men were fathers by 30.

And then, changes happening in activist circles went mainstream—women flooded into the workforce, cohabitation before marriage became acceptable, grad school attendance exploded, and, over time, our society was introduced to young adults untethered by parental responsibilities.

Young adulthood became a time of exploration for the middle and upper-middle classes. Baby Boomers encouraged their children to do things differently. Rather than spending this precious time raising small children or climbing corporate ladders, they were encouraged to explore and experiment. No longer would youth be wasted on the young. “No wrong moves” was how one millennial described the messaging she got from her mom in her early twenties.

Elizabeth Segran reflects on her twenties in her book, Rocket Years: How Your Twenties Launch the Rest of Your Life: “Life seemed so fluid and full of possibility. I saw my twenties as a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to explore the world, take plenty of risks, and make mistakes.” Of course, as Segran also points out in her book, risk-taking and mistake-making are often privileges unfairly distributed based on race and class.

Aimee echoed Segran’s sentiment. In the midst of wild nights, questionable sexual partners, and tiny apartments with four roommates, she waitressed, did data entry, moved on to a role in marketing, and then, at 30, moved to her hometown of Raleigh to “start getting serious.”

From exploration to definition

In the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, there will most likely be a YOLO vibe as young people reclaim lost rites of passage, but once the pendulum swings back, young adulthood will start moving in a different direction. The YOLO ethos of millennial young adulthood may not work quite as well in today’s increasingly competitive, unequal, and documented environment. Waiting until 30 to start getting serious may feel too late.

In her book, Jay describes how the decisions we make in our twenties define the rest of our lives more than any other decade. By the time you turn 30, your path is taking shape. If you haven’t been intentional about your direction, it can be difficult to course correct later on.

Although I don’t always agree with the author, I do admire her disregard for the “age is a state of mind” obsession in American culture as she explores the realities of neurology, biology, and cognition. She makes a compelling case that the twenties are supremely consequential, and our society has done a disservice to young people by telling them that they’ve got nothing but time.

The notion that the twenties are, in fact, “defining” seems like a concept inherently understood by many twentysomethings in my focus groups today. And this is distinctly different from what I heard from similarly aged people ten years ago. The twenties have transformed into a time to define and solidify who you want to be moving forward and ensure that you’ve captured enough identity capital to explode into adulthood armed with calculated preparation. Decisions seem more consequential, more public, and more permanent.

Gen Z writer Terry Nguyen said in an interview with Anne Helen Petersen, “I think the idea of being young and carefree no longer applies to our current reality. I feel old and weary.”

Avoiding earlier mistakes, perhaps making their own

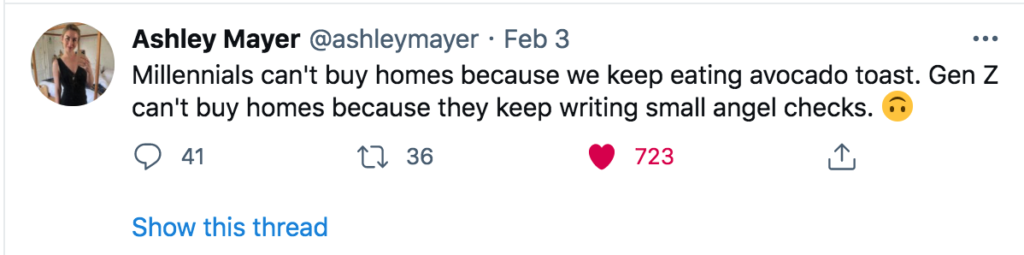

After seeing millennials financially overextended, underemployed, and remaining single longer, a new generation is stepping into adulthood with a different set of priorities. There is more consideration given to the marketability of specific majors. Fewer graduates are majoring in English, history, foreign language, or liberal arts now versus ten years ago. Healthcare and engineering, two industries known for stable career opportunities, have seen the biggest gains on college campuses.

According to the Chronicle for Higher Education, today’s college students are “more practical and more focused on relevant academic programs and support services than on bells and whistles. They shop for good value, appreciate price transparency, and want to estimate their return on investment as specifically as possible.”

Use of drugs and alcohol is down. Teen pregnancy is down. Young adult interest in long term relationships is up.

In a bakery in Birmingham, Alabama back in 2017, I sat with a group of 10 young people. A young man named Alex told me,

“I learned at an early age that there are people all over the world who can do what I can do, maybe better, and maybe for less. Maybe that’s why I became so competitive. My parents also lost a lot of money in the recession, so I need to start making money and being responsible now.”

A young woman in Los Angeles told me that during casual conversations with friends, if someone shares a particularly interesting story, someone may comment, “That would make a great interview story!” Employability and marketability are always humming away in the background.

Some partying, casual sex, and a life stage with fewer obligations remain cornerstones to young adulthood, or to pull inspiration from Aimee, aspects of young adulthood will always be a bit of a “shit show.” However, a shift is in the air. A generation accustomed to a publicly documented adolescence understands that mistakes made during young adulthood can have dramatic longer term impacts. A generation learning from the generation before is making decisions with a bit more caution and intention.

The view from thirty-eight

Many of Aimee’s stories were funny and filled with adventure. She learned what she did and did not want in a relationship. She learned where she wanted to live long term. She learned how important her family was to her. In a reflective moment, she did share a few regrets: “I wish someone would have told me that my decisions would matter. I didn’t take my career seriously and now I’m in a career I fell into but never really chose. I was impulsive and emotional and I burned a few bridges.”

As millennials approach 40, a moment of introspection is emerging. At the same time that they are evaluating their past, a new generation is already evaluating their legacy.

This isn’t to say that one generation has done young adulthood wrong and another has done it right—like all generational trends, there is no right or wrong. There is only change. Gen Z inherited a story about what it meant to be a twentysomething, and in their reevaluation of that story, some aspects are kept and others thrown away. Pendulums swing, winds blow in a new direction, and the world adapts as a new generation makes their mark.